De Doggershoek Youth Detention Facility

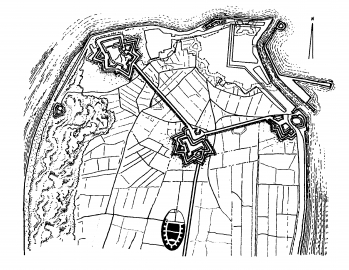

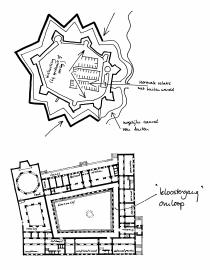

It was a paradoxical task: make a closed juvenile institute with maximum security in combination with an environment where 120 juvenile residents can receive optimal treatment. The answer is a bulwark from the outside, the forth fortress of the old seaport of Den Helder, and a monastery from the inside, a village with homes and streets.

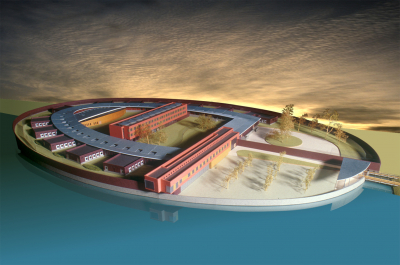

The RIJ borders on the town and rural area and is in harmony with the heritage of the old seaport Den Helder; a fourth bulwark in addition to the three existing historical forts. It is an archetype of a building where there is no relation between inside and outside: for Den Helder the building is the wall and a fort, but inside the wall the RIJ is a village in its own right.

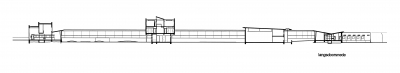

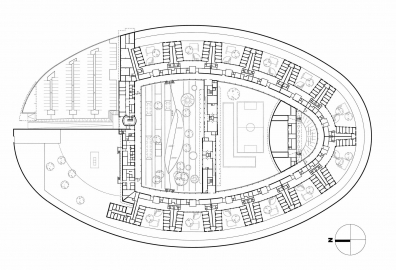

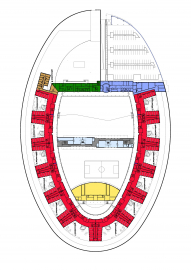

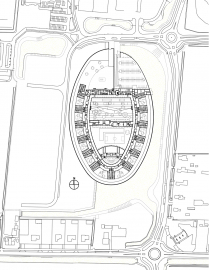

Inside the oval shaped ring wall there are 12 pavilions with living and sleeping quarters, each for 10 youths. They are situated around a walkway. Although it is a covered walkway, it is open on the side so that weather and wind can be felt during the daily walk to school and sports. The walkway connects the pavillions with the general buildings in the centre: the sportsbuilding, the education and treatment building and the general offices. Between these buildings are 3 remote outdoor areas.

ting historical forts.

With its large dimensions and heavy security, Doggershoek is a new phenomenon in the field of youth detention. The assignment was unique to such a degree that LEVS had to rethink a completely new prison typology. The design is a structured flexibly within a strong overall form, thus allowing future changes to be implemented easily. The infrastructure and the accessibility of the various components facilitate several levels of security and allow different user categories to function separately from each other.

However, the design of a youth facility required more than just handling the functional requirements. The tough framework conditions stand in dramatic contrast to the age of the target group: between 12 and 18. In extreme cases children will spend their entire secondary school period in this facility, closed off from the outside world. The underlying but possibly most important task for LEVS was thus to create a normal living and learning environment in which not only the young detainees but also the 270 members of the staff can live, learn and/or work in a safe and pleasant manner. An entire town has been developed on an area of four hectares. A walled town, with residential buildings, squares and gardens, a town hall and buildings for education and recreation. Urban planning themes such as infrastructure, the relationship between public and private space, and boundaries all play a role in this complex.

The facility has an internal oval circuit, based on the reference of the covered court passage in a cloister, giving access to all important functions. This street, although roofed, has sections with direct access to the open air so that the detainees can feel the wind and weather during their daily walks to the school and sports facilities. The public functions of the facility are situated on the inner side of the street.

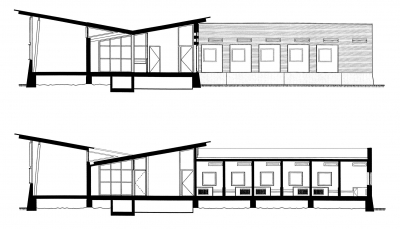

The school is a three-storey volume that cuts through the middle of the inner site. This central spot symbolises the importance of the building. In the RIJ, education plays a crucial part for youngsters to regain their place in society. Naturally schools always have a strong social function, but in a youth detention centre the societal role plays an even heavier part. Extraordinary about this juvenile centre is that it is the first one in Holland in which a complete high school was integrated. The inhabitants receive a full vocational education (beroepsonderwijs).

The design of the building translates this philosophy in architecture. The school is the only place from which the young detainees can see the outside world, symbolising a better future provided by education. Inside the building, the classrooms are situated on both sides of a high passage. On the upper floor the classrooms are connected by concrete bridges.

The activities building is a curved volume containing, among other facilities, the sports rooms and a library. In contrast to the sober school, the shape and materials of this building give it a softer feel. The entrance building is the building for staff and the gate to the outside world. The detainees enter this building only when arriving at or leaving the facility. In the garden design the symbolic distance between this building and the rest of the complex is subtly expressed by the steel poles placed in a pond. Without the use of fences or bars, a physical boundary is nonetheless achieved.

The twelve residential units are situated along the outer side of the street, built back to back and connected internally so that rapid assistance can be provided in the event of an emergency. The public character of the street is augmented by a semi-public living room shared by a maximum of twelve detainees. This living room has an elongated form that allows an element of seclusion as well. If permitted by the staff, a courtyard garden is also accessible from the living room. Each living room is connected with two residential wings, each containing five cells. Every cell has a small window with a view of the courtyard garden. In the outer facade the window units are increased in size and filled out with art projects, reducing the oppressive effect of the small cell windows.

The real boundary of the complex is a stone wall, five metres in height, which surrounds the entire site. A concrete wall, customary in such projects, was regarded by the architects as being too hard. Traditional masonry, however, provides opportunities to escape. Therefore the wall is constructed in thin-layer masonry over its entire length of more than 600 metres. This is the first time that this technique has been applied on such a large scale. From outside little more of the facility can be seen than this endless wall in the water of the polder landscape, with the upper edges of the school and the office building protruding just above the top of the wall. In this way, remarkably enough, it continues the heritage of the old port city of Den Helder as the fourth walled fortress besides the three existing historical forts. It is the archetype of a structure lacking a relationship between inside and outside, a structure that shuts itself off from its surroundings. The reference to the fort was thus ideal for the icon envisaged by LEVS, in which the wall is transformed from necessary evil to determining visual element: the wall is the building, the building is the wall.