Stage

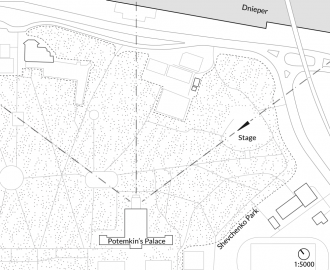

Stage is a seasonal, multi-purpose park pavilion in Dnipro, Ukraine. It was constructed in place of the former green theater in the Shevchenko Park, one of the city’s most important public spaces. Stage was created entirely with the use of crowdsourcing and crowdfunding: online methods of distributed work and funding.

How to create a truly public space?

Stage has been created entirely by citizens, using online methods of distributed work and funding. Over 200 people were engaged at all stages of its creation: contributing financially, writing the brief, designing and assembling building components. This approach is unique: architectural practice today is dominated by top-down methods of work.

At Stage, anyone can organize their own event. The lightweight wooden structure stands on the public ground, open to everyone. All borders between performers and audience were abolished. Gigantic acoustic tube amplifies any music brought to the venue. The cultural program, as well as the process of construction, has been coordinated by a local NGO. But all the ideas come from Stage’s co-creators.

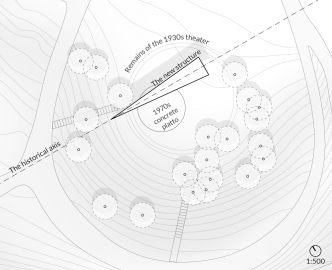

In the 1790s, Prince Grigory Potemkin built his residence in the city of Ekaterinoslavl, today’s Dnipro. The palace, surrounded by gardens, overlooked the Dnieper. In the 1920s, after the Bolshevik revolution, the city was renamed to Dnepropetrovsk. Potemkin’s palace was converted into a workers’ house; the park – into the city’s main public space. In 1935, a wooden theater for 2,500 spectators was erected in the park. It burnt down during World War II. For the next 70 years, the site remained abandoned.

After the Maidan revolution, Dnepropetrovsk changed the name again, to Dnipro. Stage is an emanation of the vibrant culture, which emerged in post-Maidan Ukraine. It was built to accommodate the needs of dozens of artists, poets, painters, and musicians, who squatted random spaces, scattered around the city. Their collective creative energy was used to reactivate the former Soviet theater.

Both Potemkin’s geometrical gardens, as well as Stalin’s gargantuan theater, were superimposed on the city from the top-down. Stage is on the opposite extreme: it is a radical grassroots intervention.

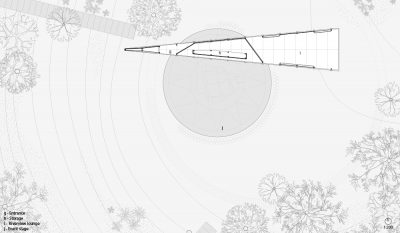

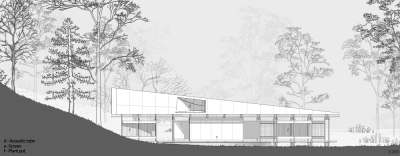

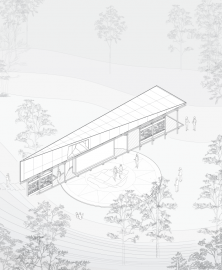

Stage’s slim volume closes the visual axis running between Potemkin’s palace and the Dnieper. The long facade encloses the amphitheatrical geometry of the site, creating a cozy interior with good acoustics. Hierarchy, inherent to the propaganda theater of the thirties, is replaced by horizontality. Location of the entrance blurs borders between the performers and the audience.

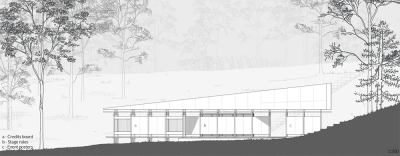

The structure consists of a big screen, storage space and a lounge, which overlooks the Dnieper. On the top there is an acoustic tube – an amplifier of any music brought by the performers. Building components from wood and plywood were prefabricated and assembled on site. Architecture is supplemented with greenery, a gift from the city’s botanical garden.

Architectural form reflects the collective character of the process. Each creative contribution has been clearly articulated in the design. All architects, designers, builders, contributors and backers are mentioned on the credits board, which is exposed on one of Stage’s most visible walls.