Archaeological Museum of Álava

Of architectures essential elements, the material is probably the only unquestionable one. In the Museum of Archaeology of Vitoria, the choice of material is intrinsically related to the idea of the project. Bronze, and its slow but inexorable aging, tells us about the passage of time.

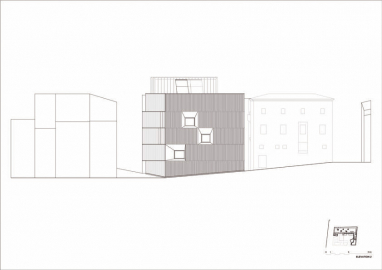

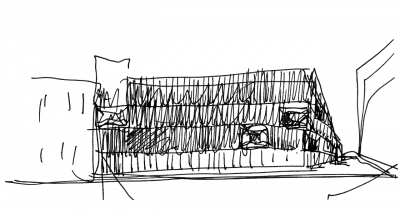

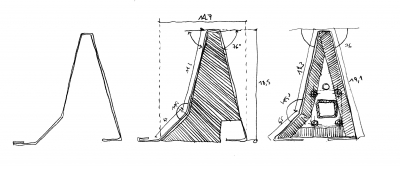

Inserted into a tight medieval warren, the museum is a dark enigmatic box obliquely perforated by four large deep-set windows. For a strong archaeological resonance, it is clad in bronze. The vertical slats of the corrugated cast.bronze carapace becomes a more open grille on the facade facing the entrance courtyard, revealing straight glass-encased stairs. The building shares this courtyard with the old palace that is home to a museum of Spanish playing cards. The enigma continues inside. Floors and walls are lined with near-black wood. Long dark rooms are lit by floor-to-ceiling leaning prisms. Vitrines are set along the walls.

An archaeology museum is a box for the treasure that history has entrusted to us piece by piece. The box, dense and hermetic on the outside, is suggestive and magical on the inside. The space within can be neither a mere organizer. It must evoke places and people from each surviving ancient fragment.

In the exhibition halls, horizontal surfaces are dark: wooden floors almost black, continuous ceilings too. The passage of time is evoked, concentrated in layers of earth forming the thick walls of history. The dark spaces are traversed by white glazed prisms drawing light in from the roof.

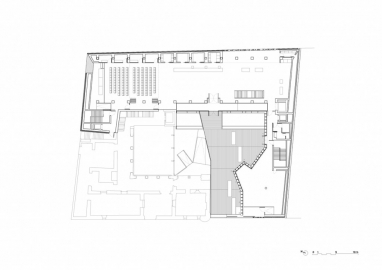

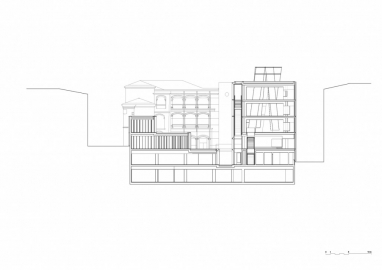

The building adjoins the Bendaña Palace, currently the Naipes Fournier museum of playing cards. Access is through the same courtyard leading to the palace. To expand the courtyard and upgrade the access area, the proposal does not take up the whole surface available, only a strip, built as an appendix to the main building. The terrain is sloped, so the courtyard is reached through a bridge that lets light into the lower areas.

Work areas and the library are on ground level. The assembly hall and temporary exhibition galleries are at the public-entry level shared with the Fournier museum. Permanent exhibitions are upstairs. The stairs define part of the facade facing the entrance courtyard.

The enclosing walls are multilayered spaces. The courtyard facade is a grille of pieces of cast bronze. A double-layered wall of screenprinted glass contains the stairs overlooking the courtyard. The facade fronting the lower street is hermetic, made of an outer layer of opaque prefab pieces of cast bronze, with openings where needed, and an inner thick wall containing the display stands and systems. The internal exhibition spaces are unencumbered, traversed only by translucent prisms.

Material almost always has a dimension that goes beyond the simply physical, acquiring an ideological dimension, of value judgement. It gathers aspects that have to do with context, with process or even with intellectual position. In the same way, the material configures the detail or, in other words, the first step is choosing the material.

The discovery of new materials is fascinating, as is the rediscovery of existing ones -such us bronze-, but with a great expressive capacity thanks to a new way of using or handling them: materials from other fields which clearly deserve to be looked at tw

copy.jpg)

copy.jpg)